This is my account of what happened after I made a map of people who needed help in Asheville and WNC following Hurricane Helene. All names have been changed.

Hurricane Helene hit North Carolina early on a Friday morning. I was up around 4:00 am, and the wind and rain were picking up in my area north of Charlotte. I wanted to hang out online with other people going through the storm. I went to Reddit and checked the subreddits for Florida, Tampa, and Georgia where the worst of the storm was passing through. These online spaces were surprisingly quiet – people were posting about heavy rain and wind, but I didn’t see reports of major damage.

I saw people in these subreddits making similar comments with expectations that the storm would be worse. I pulled up the weather radar and I could see that the storm was taking a slightly different path than what had been predicted. Helene formed into a category 5 hurricane with immense speed. Because of this, experts didn’t have the same volume of data they normally do to predict the storm’s path.

On Thursday night before the storm hit, experts predicted that Helene would hit Atlanta and then cut west towards Tennessee. My area north of Charlotte was on the edge where predictions went from, “it will be a bad thunderstorm,” to, “shit might get intense.”

On Friday morning, I watched the radar with alarm as the storm was cutting a more easterly path. It didn’t hit Atlanta – Helene threaded the needle through western Georgia. Then, the eye of the storm was headed right over western North Carolina. North Carolina’s mountains and foothills would receive the “dirty” right side of the hurricane which is most likely to contain tornadoes and severe wind gusts.

I jumped over to the Asheville subreddit, and I found storm chatter. It was around 5:00 or 6:00 am, and people were commenting in a hurricane megathread that the winds and rain were hitting hard in different neighborhoods. I was jumping between Reddit and a weather app, and as the eye of the storm got closer, I saw an interesting pattern emerge in the megathread.

What had been the usual mish-mash of online comments turned into an orchestrated reporting effort. First, there was a string of comments about trees coming down, some on people’s houses. Then, a string of comments: transformer blown; transformer just blew; heard a pop – transformer out.

The megathread took on a tone of urgency and fear. People shared mandatory evacuation orders, but some people said they couldn’t get out because trees were down. Confusion. Reports of landslides and floods.

And then, the Asheville subreddit went dark.

After the storm

Those of us outside the worst of the storm’s path would soon learn that Asheville and WNC’s entire communications infrastructure had been taken offline. Not only was there no electricity, phone service, or cell service – the physical grids and infrastructure had been wiped out.

On Saturday afternoon after the storm, a handful of people began posting in the Asheville subreddit and in Facebook groups for WNC communities. I watched helplessly as people described being stuck in landslides, trapped in their homes, and unable to get through to 911.

I have some familiarity with post-disaster landscapes, and I could see that a small volunteer army was mobilizing in central and eastern NC. Groups like the United Cajun Navy, Operation Airdrop, and many others were organizing aircraft to find survivors and deliver supplies.

That day, Buncombe County released a form to report missing people. I heard that they received thousands of submissions within the first several hours. On Saturday evening, someone who works in Buncombe County government used their personal Reddit account to share a spreadsheet with 100 entries from those submissions that had been marked “urgent.” Their post title was, “Asheville – help us find these people.”

I looked at that spreadsheet, and again, some of the reports included addresses. At this point, it was clear that people couldn’t reach 911, and if they could, the counties and cities in WNC had been absolutely devastated.

Now, weeks after the storm, we know that there were nearly 1,900 landslides in the impacted region. Now, we know that dams failed, mountains fell, and the rivers cut entirely new paths through hollers and valleys to take out hundreds of homes and entire roads. At the time, we didn’t know any of that – only that the situation seemed extremely dire due to the lack of information.

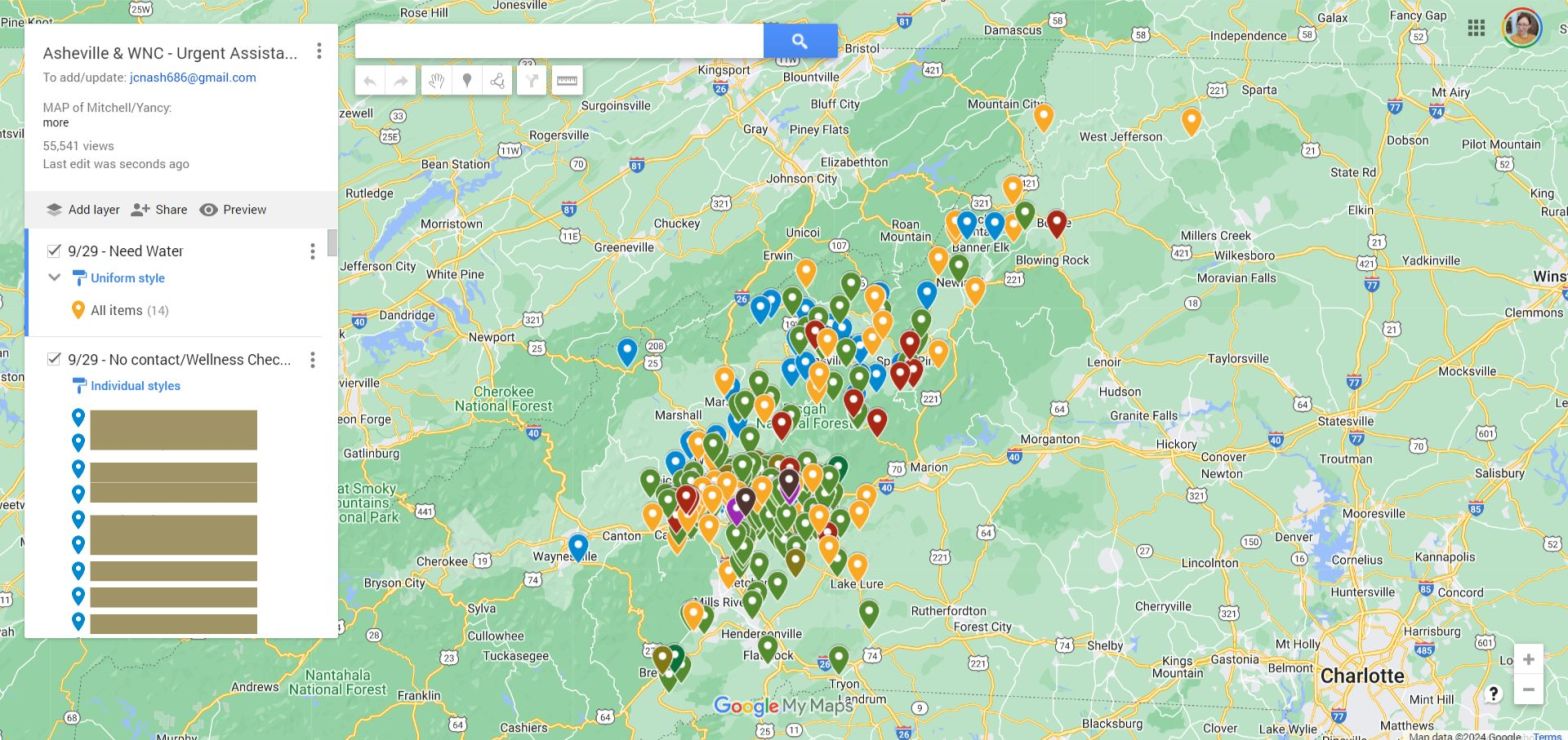

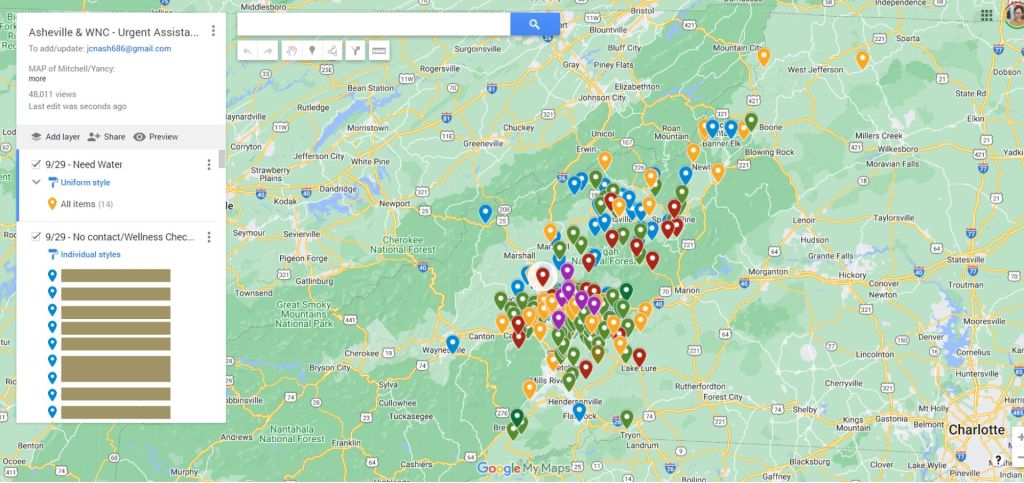

On Saturday night, I looked at the spreadsheet from Buncombe County again, and I made a Google map. I dropped red pins for the people who had locations in their requests for urgent help. On Sunday, I shared the map in a Reddit post, and I started sending it to search and rescue groups that I found on Facebook.

It’s hard to describe the chaos of the days that followed Helene. There was almost no communication within the impacted region. Dozens, if not hundreds, of volunteer crews were simultaneously moving into the area – but none of them knew where to go or were in communication with each other.

When I made the Google map, I figured it would be accurate for about 48-72 hours. I didn’t have a method to keep it updated, and I expected that there would be some obvious sign that a state or federal entity was managing the situation. I joked with my husband, “Maybe I’ll get a call from FEMA telling me to cut the crap.”

The map keeps growing

However, as Sunday and Monday progressed, the map began gaining traction on Reddit. People made comments, sent DMs, sent emails, and text messages with more reports that they needed help. I was the only person with access to update the map, and I added pins as quickly as I could.

As people in Asheville gained internet access, they began using the map to check on people near them. Other Redditors spontaneously helped me to verify and follow up on reports.

One of the first people I connected with was a guy named Andrew who lives south of Asheville. He saw a pin at the Irene Wortham Center – this is a residential home for disabled adults. Someone else had reported that they needed water and gas for generators. Andrew got them water and gas over the course of several days, making sure their generators could keep life-saving equipment running.

At the same time, I made contact with people who were managing maps and lists of missing people in Yancey, Avery, and Mitchell counties. Over late-night Zoom calls and Facebook chats, we compared data and shared phone numbers of people to connect with. It was a race to collect, document, clean, and update data, and we opened up the taps to share our information with each other. We all knew that losing this race meant people’s lives.

This all happened in the first week after the storm at a time when there was an urgent need to find people and distribute water, food, and supplies. However, counties and cities did not have the ability to respond because their own resources had been impacted by the storm. State and federal entities couldn’t respond because they aren’t nimble enough to mobilize that quickly, and in many cases, they had to clear out and rebuild roads to get to the people who needed help.

I dropped and updated hundreds of pins on the map, each one representing someone who needed help. Each pin represented multiple other people – those who made the report, those who physically checked in, those who followed up on social media, and then also people who watched from a distance because the Google map was one of the few points of visibility into a profoundly opaque situation.

The Wednesday following the storm, I got a message from someone with Florida Fish and Wildlife. Florida had dispatched them to help since they are one of the state’s leading hurricane relief agencies. I spoke with a guy named Roger, who was leading a crew.

In static-filled calls, he explained that the official chain of command didn’t know shit, and his guys needed to know where to go. He found my map and needed to know where I was getting my information. I explained that I was using first and second-hand reports from social media. Over the next several days, Roger called me to give updates on pins and different areas as his crew cleared roads and delivered supplies.

Meetings and map reading

Around this time, about five to six days after the storm, I made contact with someone with the city of Black Mountain, people with Samaritan’s Purse, Special Forces Charitable Trust, and many other groups. For days, all I did was update the map and answer questions. People had Blackhawks, fixed-wing aircraft, and heavy machinery, and they needed to know where to go.

The problem was that people in the most impacted areas still couldn’t tell us that they needed help because there was still no electricity or communications infrastructure. By this time, it was clear to me that my map was a visual representation of survivorship bias – the areas that were the hardest hit were probably the areas where there weren’t any pins.

By the Thursday following the storm, nearly a week later, I realized that I was in communication with multiple different groups – but they weren’t talking to each other. I created a nightly Regional Coordination Call.

The first night, my meeting was attended by some Special Forces guys at Fort Bragg, people from Special Forces Charitable Trust, someone with Samaritan’s Purse, a former White House advisor, and two former executives from the world’s largest paramilitary organization.

They all had Blackhawks, and I was the person with the map.

I explained to them that on the map, red pins represented an urgent need – but those pins may be less accurate since responding agencies are likely more focused on them. Yellow pins are reports of people who need supplies, and blue pins represented people who hadn’t been heard from yet.

I explained that they had to read the map for patterns. They weren’t entirely satisfied. People with Blackhawks want a certain level of veracity before spending the money to send them out, and nobody had that.

Over the next several days, I continued to update the map with a small army of people online who were sending me updates. My phone buzzed constantly with notifications and questions from search and rescue crews. The nightly meetings continued to grow. I had a conversation with the president of the Special Forces Charitable Trust after one meeting where he asked me, “So, who’s in charge here?”

I responded with something like, “That’s a great question, sir, and I’d love to ask you the same thing.” He gave me his direct cell phone number with instructions to call him if I had new insight on where to send his resources.

It quickly became clear – again, due to a lack of information – that the official response was in shambles. To be fair, it is difficult for any region to prepare for an apocalypse. At the same time, groups with search and rescue capabilities were getting in each other’s way, not communicating, and not getting to people who needed help.

Extended chaos

I don’t use the word apocalypse here lightly. I read an article recently from an expert who said that Helene wasn’t just a weather event – it was a geologic event. The landscape changed in ways that people don’t usually witness.

Neighborhoods and communities are gone. I-40 between NC and TN will take months to fully rebuild. Eight weeks after the storm, Asheville finally has potable water. In more remote areas, it will be months before all of the roads, bridges, and utilities are fully restored.

Nearly two weeks after the storm, the sky over my house was clogged with air traffic. At that point, a mid-air collision seemed like an inevitability. After I started holding nightly coordination calls, I quickly had green berets and army people entirely up my asshole. While many of these folks were active duty, they were acting in a volunteer capacity. There were some official deployments of green berets from Fort Bragg, but the landscape of official vs. unofficial duty remains extremely blurry to me.

The army people were looking at my map and using words like “money maker” and “intelligence product.” One former executive from the paramilitary organization called me directly several times to discuss updates in my map as it progressed. A former white house advisor called me when one of his pilots was shot at from the ground.

Another organization I was working with narrowly avoided a confrontation with a group of armed people in a remote area. The situation on the ground was shifting faster than anyone could keep up with, and rumors and propaganda were spreading like wildfire.

I was put in touch with many people by a couple of key army folks working behind the scenes. One of them, Mike, recognized the importance of the map and the network of people I had built, and he pulled almost every string in his network. He threw people at me, like Chris, who had almost a decade of experience in Navy intelligence.

I want to take a moment here. Before all of this, I was vaguely familiar with the green berets. I quickly came to learn that these are the people that get sent into war zones to mobilize and train insurgent (aka guerilla) forces. The people I was working with had been in Afghanistan and similar situations.

What Mike and the other green berets realized is that I had effectively mobilized a guerilla force for the purpose of disaster relief. And in doing so, I turned their entire method on its head. Normally, their method of organizing is top-down – in other words, people with resources (such as green berets) arrive in an under-resourced area and tell people without resources (such as insurgent forces) what to do.

The system that I applied was the opposite – people without resources (those impacted by Helene) were telling people with resources where to go and what to do via the Google map. And because the Google map was public, everyone could see it. Since there was no centralized chain of command for the dozens of responding agencies, the map became what the army called the Common Operational Procedure: the thing everyone could reference to plan their operations and move resources.

Rescue turns into recovery

A week after the storm, we were still hoping to find people alive. The people running search and rescue crews suspected that there were remote areas that hadn’t been reached yet, but people in remote spots were also likely to be more well-supplied than people in cities. There was hope, but time was running out. We needed to know where to send the people who could perform high-level search and rescue, field medicine, and air evacuations.

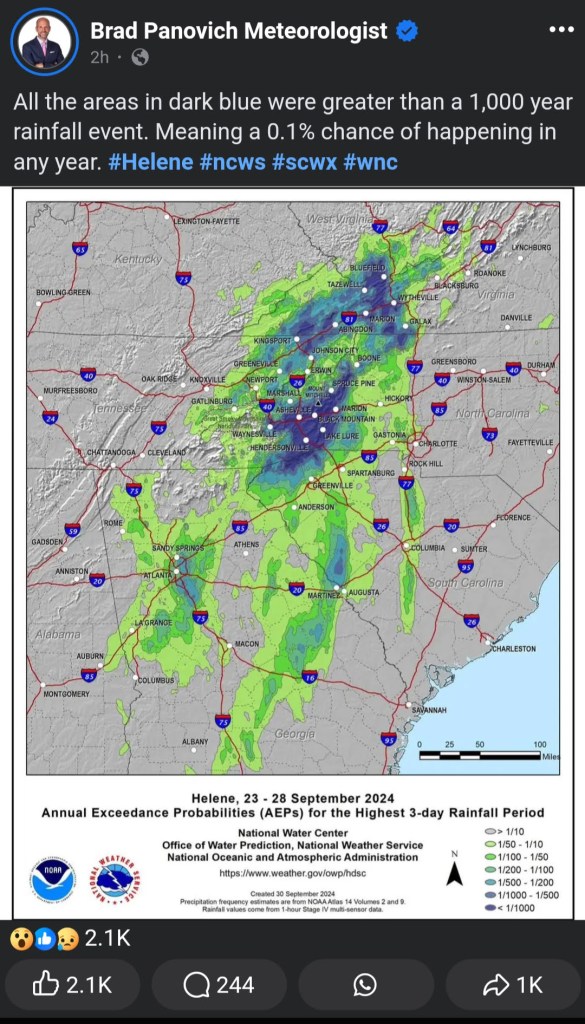

Around this time, a meteorologist I follow on Facebook shared an image of max rainfall totals in the WNC region from Helene. I looked at the image side-by-side with my map. My heart sank. I could see where I had a few outlying pins on the edges of the storm – but there were entire regions of heavy rainfall that weren’t represented with pins. These doughnut holes were probably the hardest hit areas.

This was the best confirmation I could find that my survivorship bias theory was correct. For days, I had been telling people to go to Marshall, Pensacola, Spruce Pine, and north towards the Tennessee border. People asked me why, there weren’t pins there on my map. I would say, look at this pattern – this isn’t a lack of need, it’s a lack of data.

When I saw the rainfall map, I called the navy intelligence guy. I sent him a screenshot, and I heard it in his voice. He saw it, too. I told him, we need to overlay my map with rainfall totals and max wind speeds. Add topography and street views. I told him – look at the map, and find places where you have roadways next to waterways with elevation changes. That’s where the landslides are.

Follow those roads into the hollers and valleys – that’s where the people are. I told Chris, we have the information we need to find these people. We just have to put it together. I told him to follow the Nolichucky and Watauga river basins – go downstream and zoom in on the map. I pointed out specific clusters of roads and communities.

Chris assembled his own group of navy intelligence people, and they came up with a model that I’m assuming went straight to the military. He called it an “intelligence product.”

Around this time, 7-10 days after the storm, search and rescue was transitioning into recovery. The nightly meetings grew to include people with cadaver dogs along with groups with aircraft and machinery. I was also growing a huge network of people in different communities throughout the region as they came online. I connected with people in Boone, Asheville, Spruce Pine, and many other places – some through Reddit, some through Facebook, and some through word of mouth.

The nightly meetings were a surreal mixture of people. Because I was running the meetings, I could invite whoever I wanted, and I worked hard to get community organizers into the room. It is shocking to me how candid people with official agencies were in these meetings. Because of this trust, our network was able to connect with people who had not yet been reached, make deliveries of infant formula and insulin, and mobilize volunteers and heavy machinery to communities around Boone.

I was able to create a space for people in impacted areas to say, “We need this exact kind of help,” and people with the ability to respond heard them and made it happen. And at so many points, the people we needed were the people we found.

I connected with a woman named Allison who has a background in watershed management and lives near the NC-TN border. She made it through the storm, found the map, came to meetings, and because of her guidance and expertise, the military-adjacent people got her connected with the EPA in order to point out potential trouble zones. Allison got a jump start on soil and water testing at a time when it was desperately needed.

A quick note about Allison. She is one of the most powerful people I have ever encountered. Just a total force of nature. She showed up to these meetings and made demands from a place of truth and righteousness. And people listened.

Because of her network, we connected with mapping and GIS experts who helped turn the Google map into a map on ARCgis that let us include more information for responding agencies while protecting people’s sensitive data.

Allison got us in touch with a land conservation director in the Highland area who is connecting local landowners with a program that can put cash in their hands and help prevent people from needing to sell to developers. When propaganda about landgrabs started to circulate, this was crucial information to help quell people’s (extremely valid) fears.

The trauma sets in

I need to pause here. I don’t think I’ve said enough about the absolutely wild faith and blind trust that drove all of us during this time. Everything moved so quickly, I had no idea who I was talking to at many points. I still don’t.

Another important element here is inconsistency. Even though the Google map and our network of people were surprisingly strong, we didn’t have anything close to the full picture. For every report, there were multiple, conflicting reports. Someone heard that a town needed food. Another person saw that FEMA was already there. Nobody knew what to believe, and the confusion was unrelenting.

This is where I developed the next theory: the relief effort had become a last-mile problem. Supplies were making it to centralized locations, but there was no coordinated effort to make sure those supplies were making it into the actual hands of the people who needed them.

To add to this, many of the “last miles” were still inaccessible. Roads to a local church or supermarket may have been cleared, but roads beyond that may still be covered in trees, downed lines, mud, or be washed away. Or, a person may not be able to leave their house due to illness, injury, or fear or leaving their property.

On top of that, one agency might talk to a fire chief who says their community is fine and doesn’t need any supplies or volunteers. But another agency might talk to a preacher who says they have residents who need medical supplies or are still cut off.

I emphasized to people with relief groups and the military that this effort was going to depend on local community-based groups. Fire and police chiefs aren’t going to give accurate information to outsiders. But if we connect with people who run the local Sunday schools and food banks, then we will know who still needs help.

When Helene hit, the storm shattered our physical communications infrastructure, but it also violently tore apart communities, families, and the energetic ties that hold us all together. But for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. In the days that followed, it felt like there was a great divine push to reforge those connections. Those connections were built on trust, pulled from wells far deeper than I can access on my own.

I don’t know how we knew we could trust each other, except that there wasn’t any other choice. In the two weeks following the storm, the situation on the ground was changing by the hour. We all just had to trust that we were doing our best with the information we had.

Somewhere around the 10-day mark, I realized that the secondary trauma I was experiencing was becoming a traumatic experience for me. The moment came when I received an email that someone on the map was deceased.

I was able to push through to around 17-20 days after the storm.

For most of those days, I slept four or five hours at night, and then was glued to a chair. My knees hurt from not moving. I was sick from stress and dread. I updated the Google map, answered messages, talked on the phone, and let information flow through me at a rate I hadn’t previously experienced.

The transition

Around the 2-week mark, the association with the military became more defined, but not any more transparent. Mike had been my primary point of contact for the official military, but he was acting as a volunteer and was about to be deployed. James transitioned into the military-volunteer liaison role.

I have a lot of respect for James, but I also think that the military kind of took over my thing and broke it. I’m being somewhat hyperbolic, but I don’t think James really understood that the value of the network I built – that is, accurate, actionable information – came from people in local communities.

As he worked to solidify the network at the top, there was a shift away from maintaining communication with people in local communities. The original Google map was no longer the primary tool, but the community organizers within our network were eager to keep growing. However, James was hesitant to have anything like a website, social media, or even standard boilerplate “This is what we do” language for the volunteer network.

While being a completely unaffiliated group of individuals worked for a period of time, now that the network was solidifying into its own thing, people on the outside were asking questions like, “What is your group? What do you do?” The connection to the NC National Guard was “spoken, not written” so for about a week, the entire situation felt…at odds with itself.

The breakdown

This is the point where I tapped out. I wasn’t holding it together mentally, emotionally, or physically. I tried to tell James that I needed more support and communication, but those things didn’t materialize.

I lost my job over this. I didn’t get fired, but I also didn’t want to quit. The people I worked for are all based out west, and the national news never really captured the enormity of the devastation here. They were tired of me taking PTO days, and I was presented with a situation that felt like, “choose this or that right now.”

So I just quit. The stress and shame from that have been big, and I regret that I didn’t figure out a better path through that situation.

For a while, I thought I could steer the volunteer network I had created into becoming a 501c3, but James wasn’t in agreement with that. So basically, I started a thing, the military decided it was useful, and then the military proceeded to tell me what I could and could not do without actually paying me or procuring the thing.

I spent many days in a devastating state of grief, depression, and anger. I’m still struggling to eat and sleep without nightmares. There is so much loss.

I think about the people represented by those pins every day, and I wonder how they’re doing. I think about the people who emailed me about their friends and family in WNC — some from as far away as Canada. I think about Andrew in Shiloh and all the people on Reddit who used the map to check on people around them. I think about the people who joined our nightly meetings from throughout the region, their voices hoarse from endless phone calls and chain-smoking, and their clothes stained with mud.

I may never meet any of these people, but they’re with me every day.

What comes next

Communities in WNC have a long road ahead. Many families are still living in campers or tents, even as freezing temperatures set in. Many businesses that sustained damage are struggling to reopen. These communities need state and federal assistance, and the current level of aid is simply not enough. Although Helene brought historic levels of damage across a huge swath of the southern U.S., this has been a strangely private event due to the lack of national attention.

My heart aches for the people who perished and for those who lost their homes. It’s not fair that life has to go on after such devastation, and even less so when “getting back to normal” means rebuilding harmful systems and institutions.

There are also many questions that are left unanswered. Where is the accountability for the money that poured in through fundraising efforts? Why was state and federal aid been so fragmented and hard to access? What needs to happen in order to prioritize housing and long-term security?

Despite the confusion and trauma, I keep coming back to the brilliance of human beings. The mountains fell, and people held out their hands to catch each other.

People grabbed chainsaws and shovels to reach each other. They built bridges out of debris. They slogged through mud and hiked over demolished roads to knock on doors and deliver supplies. And they did all of this while enduring their own hardship and grief.

The need is still dire in many places. Not only is there a need for housing, water, food, and physical resources — communities in WNC need to grieve and heal. But like the Google map illustrated, people will find each other, even in the most difficult of circumstances.